Supercharging a diesel engine sits right at the intersection of engineering curiosity and hardcore performance tuning. Diesel powerplants already enjoy a reputation for massive torque, long life and impressive fuel economy, yet the idea of adding a belt‑driven blower still crops up regularly in tuning forums, tractor pulling paddocks and high‑end dyno shops. The question is not whether you can bolt a supercharger onto a diesel – that is absolutely possible – but whether it makes technical, financial and practical sense for the way you use your vehicle. Understanding how superchargers interact with compression‑ignition engines, and how they compare with turbos, is essential before you start sketching brackets and pricing pulleys.

From heavy industrial two‑stroke Detroits to wild compound‑boost street trucks running four‑figure horsepower, forced induction on diesel has gone far beyond factory single turbos. If you are chasing instant throttle response, smoke‑free low‑rpm torque or a unique project that stands out from the usual “big turbo TDI”, a properly engineered supercharged diesel can deliver exactly that – provided the design respects the limits of the bottom end, fuel system and cooling package.

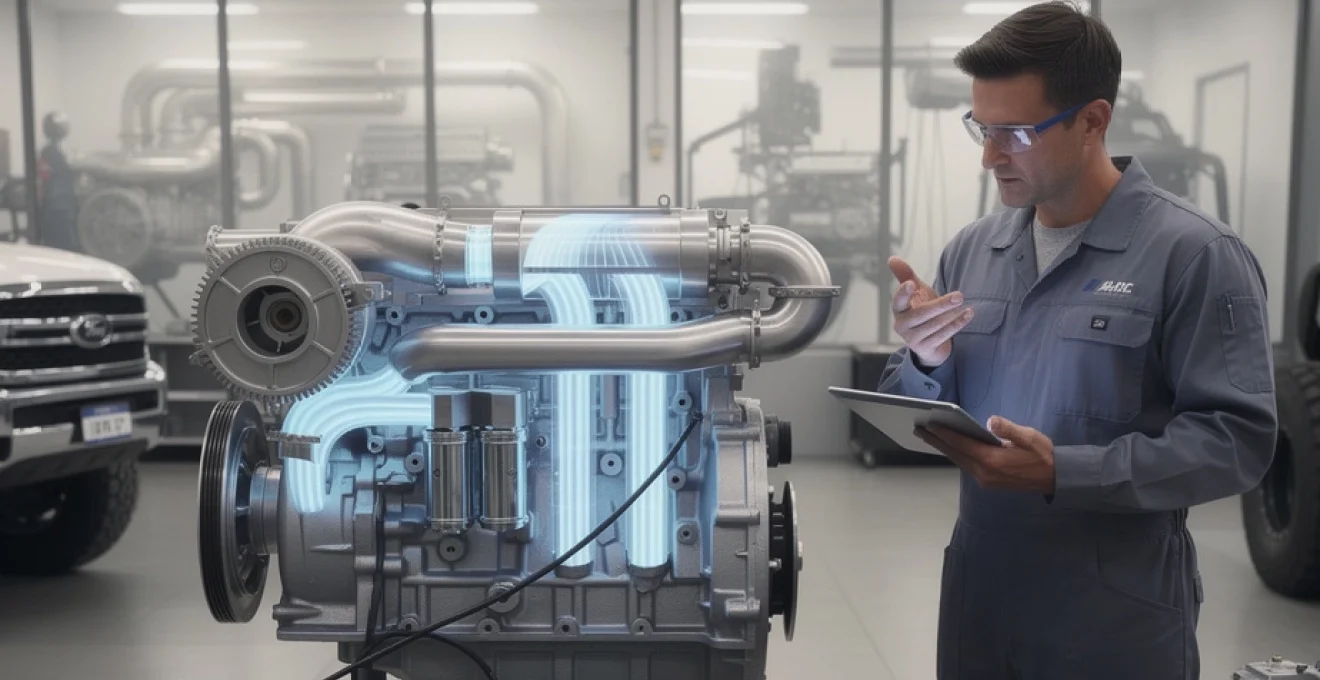

How superchargers work compared with turbochargers on diesel engines

At the simplest level, both superchargers and turbochargers are air pumps that increase intake manifold pressure, allowing more fuel to be burned and more torque to be produced. The key difference is how they are driven. A supercharger is mechanically linked to the crankshaft via a belt or gears, while a turbocharger is powered by exhaust gas energy that would otherwise be wasted. On a diesel, where efficiency and durability are paramount, that distinction shapes almost every trade‑off you need to consider before planning a supercharger conversion.

Positive-displacement vs centrifugal superchargers in diesel applications

Superchargers fall into two broad families: positive‑displacement units such as Roots and twin‑screw designs, and centrifugal units that behave more like the compressor half of a turbo. Positive‑displacement blowers deliver near‑instant boost and a roughly linear pressure rise with engine speed. For a road‑going diesel, that means strong boost right off idle, ideal for a heavy towing rig or off‑road 4×4 that needs immediate response. Many OEM petrol engines (and a few experimental diesels) use Eaton TVS or similar positive‑displacement units precisely for this predictable, low‑rpm behaviour.

Centrifugal superchargers are more efficient at higher pressure ratios and higher rpm but build boost progressively with speed. On a relatively low‑revving diesel that rarely sees more than 4,000 rpm, this often means less benefit at the very bottom end – exactly where most diesel drivers want their extra torque. That said, for a compound or “twincharged” setup where the centrifugal unit feeds a large turbo, this rising boost curve can dovetail nicely with the turbo’s sweet spot.

Boost pressure, airflow density and brake mean effective pressure (BMEP) in compression-ignition engines

Diesel engines already operate with high compression ratios and high BMEP compared with petrol engines. Modern turbo diesels commonly run peak boost in the 1.5–2.5 bar gauge range (2.5–3.5 bar absolute), giving BMEP levels above 20 bar at peak torque. A well‑developed race diesel can exceed 23 bar BMEP, while high‑output petrol turbos are often limited to around 18–19 bar by knock.

Adding a supercharger increases intake air mass flow and pressure, which in turn raises BMEP if the fueling and timing are calibrated correctly. The challenge is that every extra bar of manifold pressure translates into dramatically higher peak cylinder pressure. For a road‑based engine originally designed for, say, 18–20 bar BMEP, pushing towards race‑diesel levels with a blower can rapidly expose the limits of pistons, rods, head bolts and even block rigidity if the setup is not carefully controlled.

Mechanical drive losses, parasitic load and thermodynamic trade-offs on diesel crankshafts

Unlike a turbo, a supercharger is never using “free” energy. The power used to spin the blower comes directly off the crankshaft as parasitic load. At modest boost levels (for example 5–10 psi on a street diesel), the mechanical drive loss might sit in the 20–60 hp range, which is acceptable for a strong torque gain at low rpm. At more extreme pressure ratios, drive requirements escalate very quickly. Test data from large centrifugal units shows that at around 50 psi boost, more than 500 hp can be required just to turn the supercharger.

For a diesel whose core appeal is efficiency, every horsepower spent driving a blower is a horsepower that cannot reach the flywheel or the driven wheels.

This is where turbochargers have such an inherent thermodynamic advantage on diesel engines. The exhaust back‑pressure and heat are already the by‑products of burning fuel; using that wasted energy to drive a compressor aligns perfectly with the diesel philosophy of squeezing the most work from each drop of fuel, rather than diverting mechanical power to accessories.

Supercharger vs turbocharger boost response, torque curve shaping and transient performance

Where a diesel supercharger shines is transient performance. Even a modern variable geometry turbo (VGT) has a finite spool time, especially when matched for high power on a tuned engine. During that lag window the engine may feel flat and, if aggressively fueled, will often produce visible smoke as the air‑fuel ratio dips rich. A well‑sized positive‑displacement supercharger can deliver 5–10 psi almost at idle, eliminating this dead zone and giving crisp, petrol‑like throttle response.

On the road, that translates into a very different driving experience: stronger off‑boost performance, cleaner launches and more linear torque delivery. For off‑road or towing use, the ability to pull cleanly from low rpm without waiting for boost can be more valuable than ultimate top‑end power. The compromise is that once the turbo is fully spooled, it provides higher boost for less cost in crankshaft power, which is why most high‑power diesel projects still rely on single or compound turbos rather than standalone blowers.

Mechanical compatibility: can a diesel bottom end survive supercharger boost?

Many modern common‑rail diesels – TDI, HDi, Duratorq, Cummins and similar – are impressively stout from the factory. Manufacturers expect them to run high boost pressures, high injection pressures (often 1,800–2,000 bar in current systems), and survive hundreds of thousands of miles under heavy load. However, that does not automatically mean any stock bottom end will tolerate prolonged supercharger boost on top of an already uprated turbo setup.

Assessing piston, con-rod and crankshaft strength in common rail diesels (TDI, HDi, duratorq, cummins)

Before sketching brackets for a diesel supercharger kit, a realistic assessment of the rotating assembly is essential. Stock pistons in many light‑duty 1.9–2.0 TDI or HDi engines are cast aluminium with steel ring lands, designed for stock peak cylinder pressures plus a safety margin. Heavier‑duty Cummins 6BT, Mercedes OM606 or industrial blocks often use stronger forged or highly optimised cast components with much thicker crowns.

If you plan to run only mild extra boost – for example a small Eaton TVS targeting 0.3–0.5 bar over a mild turbo setup – the stock rods and pistons are often adequate, especially in lower power engines below 200–250 hp. For 400 hp+ street builds or 1,000 hp+ competition diesels, forged pistons, billet rods and even billet crankshafts are standard practice. The cost of a broken rod exiting the block is almost always higher than planning the right components at the outset.

Compression ratio, peak cylinder pressure and knock margin in supercharged diesels

Diesels do not suffer from spark knock in the petrol sense, because there is no throttle butterfly and combustion is initiated by compression rather than a spark. However, that does not mean compression ratio can be ignored. A typical road diesel might run a static compression ratio of 16:1–18:1. With high boost and aggressive fueling, peak cylinder pressures can exceed 180–200 bar, which pushes even robust designs to their limits.

Adding a supercharger to an already turbocharged diesel increases the effective pressure ratio and raises charge temperatures. For serious builds, lowering compression – for example from 18:1 to around 15:1 – via pistons or a different head gasket can restore headroom for boost without overstressing components. The goal is to maintain a safe margin between normal peak cylinder pressure and the onset of excessive mechanical stress, not to chase the absolute highest compression and boost combination possible.

Head gasket clamping force, head bolt stretch and block rigidity under elevated boost

Head gasket integrity becomes a major concern once combined boost (supercharger plus turbo) pushes into compound territory. Even without classic “knock”, high‑boost diesels can lift the cylinder head slightly as head bolts stretch under load, allowing combustion gases to escape and damage the gasket fire rings. Engines with long, thin head bolts and open‑deck blocks are particularly vulnerable when pushed far beyond stock power.

Mitigation usually involves upgraded head studs with higher clamping force, careful torque procedures and, in extreme cases, O‑ringed blocks or fire‑ring gaskets. If your diesel project aims for sustained high boost, a modest investment in high‑quality fasteners and machining can prevent repeated gasket failures and save both time and money in the long term.

Lubrication system capacity, oil pump sizing and bearing load with belt- or gear-driven blowers

A belt‑driven supercharger increases not only power demand but also radial load on the crankshaft nose and front main bearing. Gear‑driven setups pass those loads through the timing gears and cam drive. In both cases, the front end of the engine sees higher continuous stress than on a turbo‑only setup. The oil pump and lubrication system must support that added load, especially during long pulls such as towing on steep gradients or extended dyno runs.

Monitoring oil pressure, oil temperature and bearing condition is just as important on a supercharged diesel as logging boost and exhaust gas temperature.

For mild road builds, a healthy stock oil pump with quality oil and sensible service intervals may be adequate. High‑output engines often need higher‑capacity pumps, improved oil cooling and, in some race applications, dry‑sump systems to ensure consistent lubrication under high G‑loads and sustained high rpm operation.

Designing a supercharger system for a diesel engine: components and configuration

Designing a reliable supercharger system for a road or race diesel goes well beyond “finding a blower that fits”. Matching compressor maps, drive ratios, intercoolers and control strategies is critical. A decent rule of thumb: treat the project like a full forced‑induction development programme, not a simple bolt‑on tuning part.

Selecting a suitable supercharger type for diesel use (eaton TVS, roots, twin-screw, centrifugal)

For most diesel supercharger builds, positive‑displacement units such as Eaton TVS, roots‑type or twin‑screw designs are preferred. These provide immediate boost at low rpm, which addresses the core diesel weakness of lag at very low engine speed. Twin‑screw units also tend to have higher adiabatic efficiency than older roots designs, meaning less heat for a given pressure ratio.

Centrifugal units can make sense when you want a high airflow, high‑rpm companion for a large turbo in a compound system, or where under‑bonnet space forces a compact package. In those cases, mapping the blower to operate mainly in its efficient zone above mid‑rpm, and keeping pressure ratio modest (for example 1.2–1.5), can help avoid excessive power draw.

Pulley ratios, drive layout and boost targets for street, towing and race diesel builds

Pulley ratio is the main tuning knob that turns a supercharger from mild assist into a serious pressure maker. On a typical street diesel build focused on drivability and towing, a target of 5–10 psi from the blower, supplementing a small or medium turbo, is a sensible starting point. This might equate to a blower speed of 1.5–2.0 times crank speed at peak rpm, depending on the supercharger’s design limits.

Race diesel builds chasing extreme torque at low rpm or huge peak numbers will often run more aggressive ratios, but at that point the supercharger is best viewed as part of a compound system where a large turbo carries the bulk of the load at high rpm. Ensuring the crank pulley, belts and tensioners are fully rated for the extra torque is essential, as belt slip at high load can cause inconsistent boost and, in worst cases, belt failure and engine damage.

Intercooler sizing, charge-air cooling and intake manifold distribution on high-boost diesels

Diesel engines are particularly sensitive to intake air temperature because higher temperatures increase NOx formation and reduce charge density. A supercharger, particularly a roots‑type, naturally adds heat to the air. When combined with a turbo, charge‑air cooling becomes non‑negotiable. Large front‑mount intercoolers, water‑to‑air charge coolers or even ice tanks in competition builds are commonly used to keep intake temperatures near ambient where possible.

Intake manifold distribution also deserves attention. Uneven airflow between cylinders can lead to localised over‑fuelling, high EGTs and in extreme cases, piston damage. On popular platforms such as VW 1.9 TDI and Cummins 6BT, aftermarket manifolds with improved flow balance can complement a supercharger setup, ensuring each cylinder benefits evenly from the extra air mass.

Integrating supercharger bypass valves, wastegates and boost control strategies

A well‑designed diesel supercharger system almost always includes a bypass valve. At light load, cruise or high rpm when the turbo is doing most of the work, bypassing the blower reduces the parasitic loss and stops it from becoming a restriction. Think of it as declutching the supercharger aerodynamically, even if the mechanical drive is still turning.

In compound setups, turbo wastegates, blower bypass and sometimes variable geometry turbine control are orchestrated together by the ECU or a standalone controller. The aim is to control drive pressure and overall intake pressure ratio without creating excessive exhaust manifold pressure (often known as EMP) that can hurt reliability and spool. Well‑mapped systems transition smoothly from supercharger‑dominant to turbo‑dominant operation as rpm and load rise.

Packaging constraints in popular diesel platforms (VW 1.9 TDI, mercedes OM606, cummins 6BT)

Physical space is often the limiting factor on road cars. The VW 1.9 TDI, for example, sits transversely in a tight bay, leaving limited room for an extra blower, pulleys and custom pipework without relocating ancillaries. In some projects, the supercharger ends up where the air‑conditioning compressor or power steering pump would normally live, which introduces obvious compromises.

Longitudinal layouts such as Mercedes OM606‑powered cars or Cummins 6BT trucks offer more scope for creative brackets and drive layouts, but even there, bonnet clearance, radiator position and front chassis members can restrict options. Cardboard mock‑ups, 3D scanning and CAD design are increasingly used by professional builders to validate packaging before cutting any metal.

Twincharging and compound boosting: combining a supercharger with a turbo on diesel

Many of the most successful supercharged diesel projects use the blower not as a standalone compressor but as part of a compound or twincharged arrangement. Done correctly, this combination can offer near‑instant low‑rpm torque with the towering top‑end power that only big turbos can provide, especially in engines designed for tractor pulling or competition drag racing.

Sequential vs parallel compound setups on diesel: airflow mapping and pressure ratio stacking

Compound boosting on diesel usually means stacking pressure ratios in series rather than splitting flow in parallel. In one common layout, the supercharger feeds compressed air into the turbocharger’s compressor inlet. At low rpm, the blower does the heavy lifting. As exhaust energy rises, the turbo adds its own compression stage, raising overall manifold pressure without requiring the supercharger to work across an extreme ratio.

Alternative designs use the turbo to feed the supercharger, but this is generally less efficient and can over‑speed or over‑pressurise the blower unless an effective bypass is provided. Parallel twincharging (where both compressors feed a common plenum separately) is rarer on diesel because matching and control are more complex, and the exhaust‑driven nature of turbos already suits the diesel duty cycle so well.

Real-world twincharged diesel examples (VW 1.4 TSI-based concepts, custom cummins compounds)

Although the famous VW 1.4 TSI twincharged engine is petrol‑powered, its concept has inspired a number of diesel experiments, especially in custom builds. In the diesel space, the most visible examples are often custom Cummins or Power Stroke trucks where a roots or twin‑screw blower augments one or two large turbos in towing or drag applications. Power figures above 1,500 hp are not unusual in top‑tier competition, with compound pressure ratios well above 4:1.

These projects demonstrate that, from a purely technical perspective, there is nothing about a diesel that prevents successful twincharging. The limitation is almost always cost, complexity and packaging rather than fundamental combustion issues. For a daily‑driven road car, the same money could often buy a factory 3.0 TDI BMW or Audi with stock 250–300 hp and strong reliability, which is why most enthusiasts reserve diesel twincharging for specialised builds.

Managing exhaust manifold pressure, drive pressure and EGT in compound-boosted diesels

Compound systems create immense drive pressure on the turbine side, particularly if the turbine housing is undersized or if boost targets are aggressive. When exhaust manifold pressure significantly exceeds intake pressure (for example a 2:1 EMP:boost ratio), pumping losses rise, EGT (exhaust gas temperature) increases and overall efficiency suffers. On a diesel, sustained EGT above roughly 900–950°C can threaten turbocharger and piston longevity.

Good practice includes choosing turbine housings and wheel sizes that keep EMP under control, using high‑flow exhaust manifolds and downpipes, and monitoring drive pressure alongside boost and EGT on the dyno. In many successful builds, the turbo is sized to operate efficiently at higher rpm while the supercharger covers low‑rpm response, rather than asking both devices to operate at their absolute limits across the entire rev range.

Fuel system, ECU calibration and emissions control with a supercharged diesel

A supercharger alone cannot create power. Extra airflow must be matched with a fuel system capable of delivering proportionally more fuel, and engine management that can meter that fuel cleanly throughout the rev range. On modern common‑rail diesels, this means injectors, pumps, rail, sensors and ECU calibration all need attention.

Upgrading injectors, high-pressure pumps and fuel rail capacity in bosch common rail systems

Most current diesel cars and light commercials use Bosch‑type common‑rail systems operating at 1,600–2,000 bar. Stock injectors and pumps are normally sized for factory power outputs plus a safety margin, leaving some headroom for a remap and modest turbo upgrade. Once airflow rises significantly due to a supercharger or compound setup, the fuel system quickly becomes the bottleneck.

Upgraded injectors with higher flow rates, modified or aftermarket high‑pressure pumps, and sometimes larger‑capacity rails are required to maintain pressure at high fuel demand. Excess fuel is often recirculated through coolers because the process of compressing diesel to nearly 2,000 bar heats it considerably; without cooling, fuel temperature can climb enough to affect volume, metering accuracy and component life.

ECU remapping, injection timing and lambda optimisation for supercharged diesel combustion

Effective ECU calibration is arguably more important on a supercharged diesel than on a turbo‑only engine because extra airflow is available even at very low rpm. If fueling is not reduced accordingly at idle and light load, the result can be excessive smoke and poor economy. Injection timing, pilot injection strategy and rail pressure maps all need to be revisited.

Targeting a leaner lambda (air‑fuel ratio) across much of the load range helps keep particulate emissions under control and reduces EGT. Some tuners use the blower’s predictable boost curve to shape torque output precisely for traction, gearbox protection or towing requirements, rather than simply chasing maximum figures on the dyno sheet.

Particulate emissions, NOx formation and DPF/SCR calibration under higher air mass flow

For any road‑registered diesel, emissions control must remain part of the plan. Higher air mass flow from a supercharger generally helps reduce visible smoke, which is beneficial for MOT smoke tests and roadside checks. However, the combination of higher combustion temperatures and additional oxygen can increase NOx formation if injection timing is not carefully managed.

Engines equipped with DPF (diesel particulate filters) and SCR (selective catalytic reduction) systems require recalibrated regeneration strategies to account for altered EGT and soot loading profiles. For example, a cleaner burn might delay DPF loading but lower EGT at cruise, changing how and when passive regeneration happens. Professional calibration ensures that legal limits are respected and that on‑board diagnostics do not constantly flag errors once the induction system has been radically changed.

Reliability, use cases and legal considerations of supercharging diesel engines

Fitting a supercharger to a diesel engine is ultimately a question of use case and appetite for complexity. For some applications, it is a clever way to sharpen response and broaden the torque curve. For others, a simple turbo upgrade or a different vehicle altogether provides better value, lower risk and easier compliance with road regulations.

Heat management, charge-air temperatures and cooling system upgrades for sustained load

Diesel engines already run high thermal loads when towing, hauling or climbing for extended periods. Adding a supercharger raises intake temperatures and cooling system demand even further. To maintain reliability, many successful builds upgrade radiators, fit higher‑flow fans, add auxiliary oil coolers and ensure intercooler cores are large enough for the intended duty cycle.

Monitoring coolant temperature, oil temperature, intake air temperature and EGT under real‑world conditions gives a more accurate picture than short dyno pulls. If you plan to tow heavy loads across mountain passes or run repeated high‑speed pulls, a conservative approach to boost targets, combined with serious attention to cooling, will protect the engine far more effectively than exotic internal parts alone.

Application scenarios: towing rigs, off-road 4x4s, marine diesels and tractor pulling builds

Some applications are particularly well‑suited to a supercharged diesel. Heavy towing rigs benefit from strong low‑rpm torque and clean response when pulling away on inclines. Off‑road 4x4s that crawl and climb at low speeds appreciate instant throttle control and the ability to modulate torque precisely over obstacles. In the marine world, where engines often operate at steady rpm for long periods, a carefully matched blower can help engines reach rated power without excessive turbo lag when accelerating from idle out of the harbour.

At the extreme end, tractor pulling and drag racing diesels use superchargers mostly as “torque crutches”, helping enormous turbos light quickly before the run settles into a high‑boost, high‑rpm state dominated by the turbochargers. These engines are typically rebuilt regularly, run on specialised fuels and operate far beyond what would be sane on a road car, which is worth bearing in mind if using them as inspiration for a daily‑driven project.

Road legality, MOT smoke tests and homologation challenges for modified diesel induction

Any induction modification that significantly alters airflow and fueling also changes emissions. In many jurisdictions, tampering with factory emissions equipment – including EGR, DPF and SCR – is illegal for road use, regardless of any performance gains. For a supercharged diesel to remain legal, all original emissions systems must continue to function, and the engine must pass smoke opacity or particulate tests during inspections.

From an insurance and homologation perspective, declaring the modification is essential. Some insurers categorise forced induction changes as major modifications, which can affect premiums or even eligibility. For heavily modified projects, treating the vehicle as a track, competition or off‑road‑only machine from the outset can avoid later complications, while road‑biased builds benefit from a more conservative, emissions‑aware approach that respects both mechanical limits and legal boundaries.