Exhaust gas recirculation, usually shortened to EGR, is one of the quiet heroes of modern engine technology. Hidden in the tangle of pipework and sensors, it constantly adjusts the balance between fresh air and exhaust gas entering the cylinders. That single task helps your engine cut toxic emissions, stay compliant with tightening regulations and, when calibrated well, even improve fuel economy. If you run a diesel vehicle, a turbocharged petrol engine or manage a fleet, understanding what EGR does can save you money, prevent frustrating breakdowns and help you make smarter decisions about tuning and maintenance. The more you know about how EGR works in real engines, the easier it becomes to spot problems early and separate good advice from expensive myths.

Exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) fundamentals in petrol and diesel engines

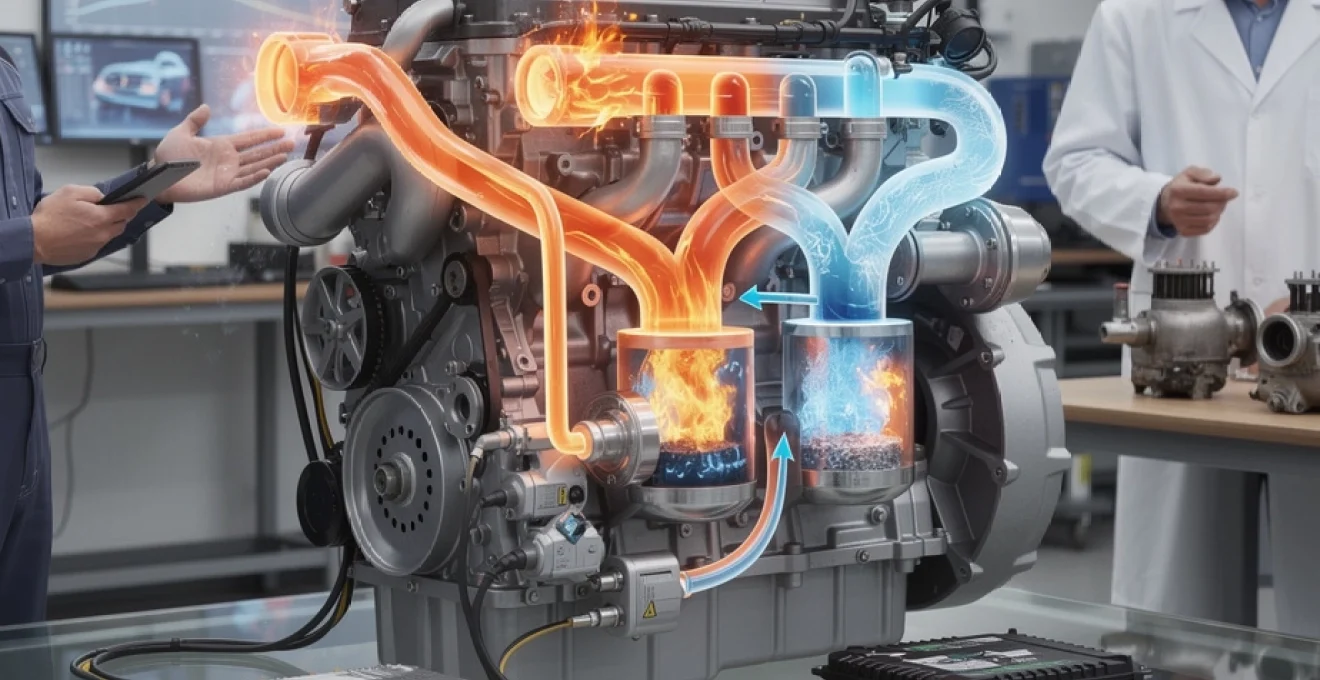

At its core, exhaust gas recirculation routes a controlled portion of spent exhaust gas back into the intake system. Instead of filling each cylinder with 100% fresh air, the engine management system meters in a percentage of inert exhaust, often between 5% and 35% depending on load, speed and temperature. This dilutes the incoming charge, slows the combustion process and reduces peak flame temperature. Because nitrogen oxides (NOx) form mainly above about 1,370°C, that temperature drop of roughly 100–150°C can cut NOx emissions by 40–60% under some operating conditions. In both petrol and diesel engines, EGR operates as an integral part of the wider engine control strategy, constantly balanced against turbo boost, fuel injection and knock control.

Closed-loop vs open-loop EGR control in modern ECUs (bosch, delphi, denso)

Modern electronic control units from suppliers such as Bosch, Delphi and Denso manage EGR with a mix of open-loop and closed-loop control. In open-loop mode, the ECU commands an EGR position or flow based on pre-calibrated maps using inputs like engine speed, load, coolant temperature and ambient pressure. This is common during transient conditions such as rapid acceleration, when fast response is vital. Closed-loop EGR relies on feedback from sensors such as EGR position potentiometers, intake manifold pressure sensors and, in some engines, differential pressure sensors across the EGR cooler. The ECU compares commanded vs measured flow and adjusts the valve accordingly. You will often see this in live data as EGR duty cycle, EGR position (in %) and calculated EGR rate.

Many Euro 6 and newer engines blend both strategies. For instance, during idle and light cruise, closed-loop control tightens NOx management and combustion stability. Under heavy load or at high altitude, open-loop EGR limits protect against misfire, smoke and turbocharger overspeed. From a diagnostic point of view, understanding when the ECU is using feedback versus prediction helps you interpret whether a fault lies in a sensor, the valve itself or the underlying calibration.

Differences between high-pressure and low-pressure EGR circuits

Most modern diesel engines use either high-pressure EGR, low-pressure EGR, or a combination of the two. High-pressure EGR diverts exhaust gas directly from the exhaust manifold, upstream of the turbocharger, and routes it to the intake manifold after the throttle valve. Pressures at this point can reach around 3.5 bar, and temperatures as high as 950°C, so robust valves, coolers and pipework are essential. Low-pressure EGR, by contrast, takes exhaust downstream of the turbocharger and after-treatment devices, often after the diesel particulate filter (DPF), and returns it ahead of the turbo compressor. Pressures are lower (typically up to 1.3 bar), temperatures are cooler (around 800°C at entry, substantially lower after cooling), and the gas is much cleaner in terms of soot content.

The choice between high- and low-pressure circuits is a trade-off. High-pressure systems respond quickly and are ideal for cold start and transient operation, but tend to suffer more from soot accumulation and valve sticking. Low-pressure systems allow larger overall EGR rates, better mixing via the compressor and improved turbine efficiency, but add complexity, cooler load and the risk of fouling the compressor with condensate or deposits. Many Euro 6 diesels therefore use a hybrid strategy: high-pressure EGR dominates at low speed and during warm-up, while low-pressure cooled EGR takes over at higher loads and steady-state cruising.

EGR operation in compression ignition vs spark ignition engines

Although the hardware looks similar, EGR plays slightly different roles in compression ignition (diesel) and spark ignition (petrol) engines. In diesels, where fuel is injected into highly compressed hot air, EGR mainly targets NOx reduction and noise control. By recirculating exhaust gas, the engine reduces oxygen concentration, increases specific heat capacity of the mixture and slows the initial burn. This not only lowers NOx but can also dampen diesel knock, especially at idle. Typical EGR rates in light-duty diesels can exceed 25–30% under part load.

In petrol engines, especially modern downsized direct-injection units, EGR is as much about efficiency as emissions. By diluting the intake charge, cooled EGR reduces pumping losses (thanks to wider throttle openings), extends knock limits and supports higher compression ratios and boost pressures. Some turbocharged petrol engines use EGR to allow spark timing closer to optimal even under high load, yielding real-world fuel consumption improvements of 2–5% in certain driving cycles. The calibration window is narrower than in diesels, however, because excessive EGR in a spark ignition engine can lead to unstable combustion, misfire and poor drivability.

Interaction of EGR with turbocharging, intercooling and boost pressure

Exhaust gas recirculation never operates in isolation; it constantly interacts with turbocharging, intercooling and boost control. When the EGR valve opens, a portion of exhaust gas bypasses the turbine, which can reduce available energy to drive the turbo. To maintain target boost pressure, the ECU may command higher vane angles in a variable geometry turbocharger or adjust wastegate duty cycle. At the same time, the increased mass flow on the intake side – a mix of fresh air and exhaust – passes through the intercooler, affecting charge temperature and density.

This delicate balance is one reason why EGR deletion in turbocharged engines often produces side effects such as increased turbo lag, higher exhaust gas temperatures and, in some cases, elevated particulate emissions. From a tuning perspective, the safest calibrations always consider EGR, boost pressure and air–fuel ratio as one system rather than isolated parameters. Thinking of the engine as a breathing system, EGR effectively adds a second “lung” loop, and changing that loop without recalibrating the rest rarely ends well for either reliability or emissions.

Chemical and thermodynamic effects of EGR on combustion

Inside the cylinder, EGR influences combustion chemistry and thermodynamics in several powerful ways. By replacing some of the fresh intake air with inert exhaust, the mixture’s effective oxygen level is reduced, slowing the reaction rate. The recirculated gas also has a higher specific heat capacity than air, so it absorbs more energy during combustion without such a steep rise in temperature. Combined, these effects stretch out the heat release curve, lower peak pressures and temperatures, and shift NOx formation towards safer levels. At the same time, EGR can change ignition delay, soot formation, flame propagation and CO/HC oxidation, which is why poor EGR calibration can increase fuel consumption or particulates even as it cuts NOx.

Nox reduction through charge dilution and peak flame temperature control

NOx emissions arise mainly via the thermal NO mechanism, where nitrogen and oxygen react at very high temperatures. Because the reaction rate increases exponentially with temperature above roughly 1,800 K, even a modest temperature reduction has a large effect. EGR achieves this by charge dilution and by using exhaust gas as a heat sink. Industry data from Euro 6 diesel calibration programmes show that increasing cooled EGR rate from 0% to around 20% under part load can cut engine-out NOx by more than 50%, before any selective catalytic reduction (SCR) takes over.

For urban driving with frequent low-load operation, that makes EGR a cornerstone of emission compliance. The strategy is especially relevant under Real Driving Emissions (RDE) conditions, where engines must meet limits on the road, not just in the lab. Without aggressive but stable EGR control, many engines would exceed NOx caps during moderate acceleration or uphill gradients. The key is achieving sufficient dilution without triggering misfire, soot spikes or combustion instability – a fine balancing act that modern ECUs handle using increasingly sophisticated models.

Influence of EGR on ignition delay, flame speed and combustion stability

In diesel engines, EGR typically lengthens ignition delay by reducing oxygen concentration and lowering charge temperature, which at first glance might seem undesirable. However, the story is more subtle. Higher EGR rates often lead to a smoother, more premixed burn phase with lower pressure rise rates, reducing combustion noise and mechanical stress. In petrol engines, EGR tends to slow flame speed, so the ECU must advance spark timing to maintain optimal combustion phasing. If EGR is excessive or poorly mixed, local pockets of mixture may not ignite properly, causing cyclic variation and rough running.

This is one reason why you might feel a slightly lumpy idle or hesitation on light throttle when the EGR valve sticks partially open. On a scope trace or cylinder pressure log, this appears as increased cyclic dispersion and erratic heat release. Well-calibrated EGR, by contrast, can actually improve combustion stability under some conditions by moderating knock and enabling more consistent burn angles cycle-to-cycle.

Impact of EGR on particulate matter, soot formation and oxidation

EGR has a complex relationship with particulate matter (PM) and soot. On the one hand, reduced oxygen concentration and lower combustion temperatures can promote soot formation, particularly in diesel engines with rich local zones in the spray plume. On the other hand, moderate EGR can also lengthen residence time at temperatures where oxidation reactions can burn off some of that soot before it exits the cylinder. Data from several heavy-duty diesel studies show a characteristic “U-shaped” curve: as EGR increases from 0% to a moderate level, soot may decrease, but beyond a threshold (often above 25–30%) soot rises sharply.

Modern engines manage this by combining EGR with advanced injection strategies, such as higher injection pressures, multiple pilot injections and optimised swirl. In petrol direct-injection engines, high EGR rates can aggravate particulate number (PN) emissions if injection timing and spray targeting are not carefully matched, which is one reason why gasoline particulate filters (GPFs) have become the norm in Euro 6d vehicles. From a maintenance viewpoint, excessive low-speed driving with heavy EGR flow and limited DPF regeneration chances is a common cause of soot build-up and eventual filter blockage.

Effects of EGR on fuel consumption, pumping losses and thermal efficiency

A well-designed EGR strategy can improve fuel consumption, particularly in spark ignition engines. By allowing a wider throttle opening for a given torque output, EGR reduces pumping losses – the wasted work required for the engine to suck air past a nearly closed throttle plate. Studies on downsized turbocharged petrol engines report BSFC improvements of 3–5% in part-load conditions when using cooled EGR compared with pure throttling for load control. In diesels, the relationship is more mixed: high EGR rates can lower thermal efficiency due to reduced combustion temperatures and slower burn, but this can be offset by optimised injection timing and reduced after-treatment load.

There is also an indirect efficiency effect through reduced after-treatment demand. Lower engine-out NOx means the SCR system or NOx storage catalyst works under gentler conditions, using less urea solution (AdBlue) and suffering less thermal stress. However, EGR can accelerate engine oil contamination by introducing more soot and unburned fuel into the crankcase, especially when combined with long service intervals. For you as an owner or technician, that makes high-quality oil, sensible drain intervals and occasional intake cleaning particularly important on EGR-heavy engines.

Hardware components in an EGR system and their functions

A modern EGR system is built from several specialised components that must work together under harsh thermal and chemical conditions. Understanding each part helps you diagnose faults and select the right replacement or upgrade. The heart of the system is the EGR valve, which meters flow between the exhaust and intake paths. Around it sit EGR coolers, transfer pipes, position and temperature sensors, and in some layouts integrated throttle or butterfly units. On Euro 6 and Euro 7 engines, these are tightly integrated with the DPF, SCR and oxidation catalyst to meet combined limits on NOx, particulates, hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide.

EGR valves: poppet, butterfly and linear electronic designs

EGR valves come in several designs, tailored to pressure, flow and packaging needs. Traditional vacuum-operated poppet valves use a diaphragm and spring to lift a valve head off its seat, controlled via a vacuum solenoid. Many older diesels rely on this layout; when carbon builds up on the seat or stem, the valve can stick partly open or closed. More recent engines often use electronically actuated butterfly or linear valves. In a butterfly valve, a rotating disc (similar to a throttle body) modulates flow in a tubular housing, driven by a DC motor and geared actuator.

Linear electronic valves use a plunger-type mechanism, sometimes with multiple ports, and are controlled directly via the ECU with PWM (pulse-width modulation) or stepper motor commands. Position feedback is typically provided by a potentiometer or Hall-effect sensor, allowing precise closed-loop control across the full operating range. Twin-diaphragm and twin-valve configurations are also used in some applications to cope with very high flow demands. From a practical perspective, understanding which type of EGR valve your engine uses determines the best cleaning method and the likely failure modes.

EGR coolers, heat exchangers and coolant routing strategies

Cooled EGR relies on compact heat exchangers that use engine coolant to reduce exhaust gas temperature before it enters the intake. These EGR coolers can lower gas temperatures from several hundred degrees Celsius down to levels safe for plastic intake manifolds and sensors, while also enhancing NOx reduction by further cutting combustion temperature. Typical designs include tube-and-fin or plate-type coolers, often with integrated bypass valves that allow the ECU to route exhaust either through or around the cooler depending on operating conditions.

Coolant routing strategies vary. Some manufacturers place the EGR cooler in the main engine coolant loop, while others use separate low-temperature circuits together with charge air coolers. This can improve thermal management during cold start and prevent overcooling, which risks condensation and corrosive acid formation inside the cooler. Common failures include internal coolant leaks (leading to unexplained coolant loss or white smoke), external corrosion, and soot fouling that restricts flow. Early detection is crucial, because a failed cooler can also contaminate the DPF and turbocharger with coolant residue.

DPF, SCR and EGR system integration in euro 6 and euro 7 layouts

In Euro 6 and forthcoming Euro 7 layouts, EGR sits alongside diesel particulate filters, selective catalytic reduction systems and oxidation catalysts in a highly integrated exhaust after-treatment chain. A typical Euro 6 diesel layout might feature high-pressure EGR before the turbo, a close-coupled oxidation catalyst, a DPF, then SCR and ammonia slip catalyst further downstream. Low-pressure EGR would then tap exhaust after the DPF and route it back to the intake side ahead of the compressor. The result is a complex network of interdependent systems: altering EGR flow changes exhaust temperature and composition, which affects DPF regeneration intervals and SCR efficiency.

On advanced petrol engines with gasoline particulate filters and three-way catalysts, cooled EGR is increasingly used to reduce both NOx and particulate number without over-relying on the after-treatment. Industry discussions around Euro 7 suggest that higher durability requirements, extended warranty periods and stricter RDE margins will further tighten this integration. That means future EGR systems are likely to be more robust, more sensor-rich and more tightly calibrated to work with catalyst ageing models and onboard diagnostics.

Position, temperature and pressure sensors used for EGR feedback control

Accurate EGR control depends on a network of sensors. At a minimum, most systems use an EGR position sensor (often a potentiometer) to report valve angle or lift. Many also employ exhaust gas temperature sensors before and after the EGR cooler, as well as coolant temperature sensors within or near the cooler body. Intake manifold absolute pressure (MAP) and mass air flow (MAF) sensors provide indirect information about EGR flow, since recirculated exhaust changes both total mass flow and oxygen content.

Some engines go further and include dedicated differential pressure sensors across the EGR cooler or orifices to estimate flow more precisely, especially on low-pressure circuits. When diagnosing EGR-related issues, comparing commanded EGR rate with inferred rate from these sensors is a powerful technique. For example, if the ECU reports high EGR duty but MAP and MAF values indicate little change, a blocked cooler or stuck valve is more likely than a sensor fault. Conversely, implausible sensor readings with normal drivability may point to wiring or sensor calibration issues rather than genuine EGR malfunction.

EGR strategies in real engines: examples from VW TDI, ford EcoBoost and cummins diesels

Theory becomes much clearer when anchored in real production engines. Different manufacturers approach EGR architecture and calibration in ways that reflect their emissions targets, duty cycles and brand philosophies. Passenger car diesels such as VW’s TDI family lean heavily on high-pressure EGR and tightly integrated after-treatment. Turbocharged petrol engines like Ford’s EcoBoost series use cooled low-pressure EGR to boost efficiency and knock tolerance. Heavy-duty engines from Cummins and Volvo combine massive cooled EGR systems with high-capacity SCR to meet Euro VI and EPA standards under demanding real-world operating conditions.

High-pressure EGR calibration in VW 2.0 TDI CR engines

Volkswagen’s 2.0 TDI common-rail engines have used high-pressure EGR for several generations, combining vacuum-operated or electronic valves with compact coolers. In these engines, EGR is particularly active during low and medium load conditions typical of urban and motorway cruising. Calibration data published in independent studies suggest that EGR rates can approach 30% under some part-load points, with closed EGR during full-load acceleration to preserve power and prevent excessive smoke.

These engines illustrate both the benefits and challenges of aggressive EGR use. When the EGR path and intake manifold are clean, NOx emissions remain low and fuel economy is competitive. Over time, however, soot and oil vapour can mix to form sticky deposits that gradually restrict flow. The driver may not notice until performance drops or a fault code appears. Carbon build-up also contributed to some well-known intake and valve deposit issues in early TDI engines, making regular maintenance and, where appropriate, periodic intake cleaning a sensible precaution.

Low-pressure cooled EGR in ford EcoBoost downsized petrol engines

Ford’s EcoBoost engines are a good example of cooled low-pressure EGR in turbocharged petrol applications. By routing cleaned exhaust gas from downstream of the catalyst back to the intake side before the compressor, and cooling it through a dedicated heat exchanger, these engines can replace some of the usual throttling with EGR-based load control. That allows the throttle to remain more open at part load, reducing pumping work and improving real-world fuel consumption.

In some EcoBoost calibrations, EGR is also used under higher load to suppress knock, allowing slightly higher boost or more advanced ignition timing without detonation. The result is a combination of strong low-speed torque and reasonable economy from a relatively small displacement. From a maintenance angle, the main vulnerability is again contamination: if the EGR cooler or valve becomes restricted, the engine may revert to more throttling, losing some efficiency benefits and triggering emissions faults.

Heavy-duty cummins and volvo diesel EGR architectures for euro VI and EPA standards

Heavy-duty diesel engines from manufacturers such as Cummins and Volvo operate under far more severe duty cycles than passenger cars: long periods at high load, high mileage and wide ambient temperature variation. To meet Euro VI and EPA 2010+ standards, these engines use large cooled EGR loops capable of flowing substantial volumes of exhaust while maintaining stable combustion and turbocharger performance. Typical layouts feature robust stainless-steel coolers, large-diameter pipework and high-durability valves designed for millions of opening cycles.

In these applications, EGR is calibrated hand-in-hand with powerful SCR systems and often variable geometry turbochargers. Under highway cruise, EGR rates may be relatively modest to preserve fuel efficiency and SCR handles the bulk of NOx reduction. Under transient or low-load conditions, EGR is ramped up to keep engine-out NOx under control even before the after-treatment system has fully reached operating temperature. Fleet operators increasingly monitor EGR effectiveness indirectly via urea consumption, fuel consumption and onboard diagnostics to minimise downtime and warranty risk.

EGR deletion, blanking plates and ECU remapping in aftermarket tuning

Aftermarket tuning communities often promote EGR deletion or the use of blanking plates combined with ECU remapping. The perceived benefits include cleaner intake tracts, improved reliability on problem-prone valves, and sometimes marginal gains in peak power or throttle response. While it is true that removing EGR reduces soot contamination in the intake and may simplify troubleshooting, there are significant trade-offs. Without EGR, engine-out NOx levels rise sharply, sometimes by several hundred percent under real driving conditions.

There are also practical risks. Blocking the EGR flow changes exhaust backpressure, turbocharger operating points and thermal loads on pistons, valves and catalysts. Poorly executed EGR deletes can lead to hotter exhaust gas temperatures, increased knock tendency in turbo petrol engines and shorter DPF life due to altered regeneration patterns. Moreover, tampering with EGR and related emission controls is illegal on public roads in many jurisdictions and can cause MOT or inspection failures. For road-going vehicles, focusing on proper cleaning, correct-quality replacement parts and accurate ECU updates is generally a far better long-term strategy.

Egr-related faults, diagnostics and maintenance procedures

Because EGR systems live in a harsh environment – hot exhaust, soot, corrosive condensate and continuous thermal cycling – they are prone to wear and contamination. Many drivability complaints, from rough idle to limp-home mode, can be traced back to sticking valves, blocked coolers or leaking gaskets. Effective diagnosis means combining fault codes, live data, basic mechanical checks and an understanding of typical failure modes. Preventive maintenance, including regular intake cleaning and timely replacement of worn components, can significantly extend system life and avoid costly downtime.

Common EGR failure modes: sticking valves, clogged passages and cooler leaks

The most frequent EGR valve failure mode is carbon build-up on the valve seat, stem or spindle. Over time, soot from exhaust gases mixes with oil vapour from the crankcase ventilation system and hardens into deposits. The valve may then stick partly open, causing rough idle, low power and excessive smoke, or stick closed, leading to high NOx emissions and potentially elevated combustion temperatures. Vacuum-operated valves can also fail due to diaphragm rupture, cracked vacuum hoses or faulty solenoids.

Clogged EGR passages and manifolds present similar symptoms. In some engines, narrow drillings in the cylinder head or intake manifold gradually plug up, reducing EGR flow even though the valve itself still moves. EGR coolers are vulnerable to both soot plugging and coolant leaks. Internal leaks may allow coolant into the exhaust stream, producing white smoke and gradual coolant loss without obvious external drips. Left unchecked, this can damage the DPF, catalysts and turbocharger. Regular visual inspections, pressure testing and, when necessary, cooler replacement are vital on high-mileage vehicles.

OBD-II fault codes (P0400–P0409) and live data interpretation for EGR systems

On OBD-II equipped vehicles, EGR problems usually trigger diagnostic trouble codes in the P0400–P0409 and P1400–P1409 ranges. Common examples include P0400 (EGR flow malfunction), P0401 (insufficient EGR flow), P0402 (excessive EGR flow) and P0403 (EGR circuit malfunction). Additional codes such as P0404 (range/performance), P0405 and P0406 (sensor low/high) point more directly to position sensor or wiring issues. Manufacturer-specific codes like P1403–P1406 often relate to EGR solenoid control or pintle position errors.

Simply reading codes is not enough; interpreting them alongside live data is far more effective. Useful parameters include commanded EGR position, actual EGR position, MAP, MAF, EGR temperature and sometimes differential pressure readings. For example, a P0401 code with high commanded EGR but little drop in MAF suggests a blocked cooler or passage. A P0402 code at idle, with MAP higher than expected, may point to a valve stuck open. Combining scan tool activation tests (forcing the valve to open/close) with vacuum gauge readings on older systems helps differentiate between electrical, pneumatic and mechanical faults.

Intake manifold carbon build-up and cleaning methods (walnut blasting, chemical treatments)

One of the most visible side effects of EGR, especially on direct-injection engines, is intake manifold and port carbon build-up. Without a constant wash of fuel over the back of the valves, oil mist and soot from EGR can form thick layers of deposit. This gradually narrows airflow passages, disrupts tumble and swirl, and can eventually cause significant power loss or misfire. If you have ever seen an intake manifold choked with black sludge on a high-mileage diesel, EGR contamination was almost certainly involved.

Cleaning options range from simple chemical sprays applied into the intake (best as preventive maintenance) to more intensive methods. Walnut blasting, where crushed walnut shell media is blasted at the valves and ports with the manifold removed, is widely considered one of the most effective solutions for heavy build-up. Professional chemical treatments, often combined with EGR valve removal and bench cleaning, can restore much of the original flow. From experience, tackling deposits before they become rock-hard saves time and money, so scheduling an inspection around 80,000–100,000 miles on known-problem engines is a pragmatic approach.

Preventive maintenance intervals and EGR component replacement guidelines

Preventive maintenance for EGR systems is rarely spelled out clearly in owner’s manuals, but a few sensible guidelines help prolong life. Using high-quality fuel and oil that meet the manufacturer’s latest specifications reduces soot formation and oil vapour contamination. Shortening oil change intervals in severe service – lots of city driving, short trips, towing – limits the build-up of contaminants that can reach the intake. Periodic intake and EGR cleaning, whether via professional chemical methods or physical removal where practical, keeps valve movement free and passages open.

As for replacement, EGR valves and coolers are increasingly treated as service items on high-mileage fleets. Many technicians plan valve inspection or replacement somewhere between 100,000 and 150,000 miles for heavily used diesels, especially where fault histories or known design weaknesses exist. When replacing a valve, following the correct adaptation or relearn procedure in the ECU is critical; skipping this step can cause position errors that lead to premature failure. Finally, always check associated components – vacuum hoses, electrical connectors, gaskets and coolant lines – during any EGR-related repair to avoid repeat visits.

Future trends in exhaust gas recirculation and emission control

Looking ahead, EGR is set to remain a major tool in the emissions engineer’s toolkit, even as electrification accelerates. Stricter Euro 7, US EPA and global RDE regulations demand lower NOx and particulate emissions under a wider range of conditions, including cold start and dynamic driving. That pressure is steering development towards more intelligent EGR control algorithms, better-cooled circuits, and closer integration with advanced combustion concepts like homogeneous charge compression ignition (HCCI) and partially premixed compression ignition (PCCI). Hybrid powertrains and 48V systems introduce new opportunities for operating the engine in EGR-friendly regions more of the time.

Advanced EGR control algorithms using model-based and adaptive strategies

Traditional EGR control relied heavily on look-up tables and simple PID loops. Next-generation systems increasingly use model-based and adaptive strategies that predict EGR behaviour under changing conditions. By modelling exhaust gas dynamics, cooler efficiency, valve hysteresis and sensor ageing, the ECU can command more accurate EGR rates without relying solely on feedback. This is essential under RDE testing, where rapid load changes and altitude variations can expose weaknesses in basic control schemes.

Adaptive algorithms can also compensate for gradual changes such as cooler fouling or valve wear, maintaining emissions compliance longer before a fault is triggered. Over-the-air software updates, already common in some passenger cars, will likely refine EGR and after-treatment control over a vehicle’s life in response to field data. For you as a user or technician, that means software versions and calibration IDs will become just as important as physical part numbers when troubleshooting EGR-related issues.

Combining EGR with advanced combustion concepts: HCCI, PCCI and RCCI

Advanced combustion modes such as HCCI (homogeneous charge compression ignition), PCCI (partially premixed compression ignition) and RCCI (reactivity controlled compression ignition) all rely on carefully controlled mixture preparation and auto-ignition. EGR plays a crucial role here by moderating combustion temperatures, extending the operating window where these low-NOx, low-soot modes are possible. By adjusting EGR rate, temperature and distribution, engineers can shape ignition timing and burn duration without resorting to excessive injection complexity.

Although full-time HCCI operation remains challenging for mass-market engines, partial use in limited load/speed zones is becoming more realistic as control hardware and software improve. In those zones, engines can achieve near-diesel levels of efficiency with petrol-like fuels, while maintaining NOx and PM emissions well below conventional levels. EGR hardware must therefore become more precise, faster-acting and more durable to cope with frequent transitions between combustion modes.

EGR in hybrid powertrains, stop–start systems and 48V mild hybrids

Hybrid and mild-hybrid powertrains change how often and under what conditions an engine runs, which directly affects EGR usage. Stop–start systems lead to more frequent restarts, increasing the importance of clean and reliable EGR valves that do not stick during cranking. In full and plug-in hybrids, the engine often operates in more efficient load zones, where EGR use can be optimised to minimise NOx without hurting drivability, since the electric motor can fill in torque gaps.

48V mild hybrids open additional possibilities, such as electrically driven compressors or e-boosters that can compensate for turbo lag while EGR is used aggressively for NOx control. Intelligent powertrain controllers can choose engine operating points that balance EGR effectiveness, catalyst temperature and battery charge state. For a driver, this translates into smoother torque delivery and lower fuel consumption, with EGR working largely unnoticed in the background, provided maintenance schedules keep up with the extra thermal cycling.

Role of EGR in meeting euro 7, real driving emissions (RDE) and WLTP regulations

Forthcoming Euro 7 rules and tightened RDE requirements will push engines to deliver near-laboratory emissions performance in real life. That means stable NOx control from cold start, during motorway climbs, in city traffic and at high altitude. EGR will remain central to this goal, especially in combination with more capable SCR and particulate control systems. Engineers are already working on faster-warming EGR coolers, better condensation management and layouts that maintain consistent EGR flow even during rapid transients.

Under the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP) and the latest RDE boundaries, engines must also handle more aggressive driving styles and a broader temperature range. Robust EGR hardware, advanced diagnostics, and predictive control algorithms will be essential to avoid emissions spikes that could jeopardise certification. For anyone buying, running or repairing vehicles over the next decade, EGR knowledge will stay highly relevant as combustion engines, hybrids and advanced after-treatment continue to coexist on roads worldwide.